隔離, 孤獨 以及不良的社會連結是導致精神疾病的關鍵因素,但我們的反應 遺跡 碎片化。在一個緊張的、醫療化的體系中,人們是根據他們的症狀和嚴重程度來評估的,而不是作為社會背景下的完整人來評估的。

護理人員坐在辦公室門外或在家等候 – 家人、伴侶、鄰居、有償和無償 – 儘管對問題和解決方案都至關重要,但卻常常被忽略。

對於那些初次面對心理健康挑戰的人來說,這個系統複雜、孤立,而且諷刺的是,它讓人感到孤立。許多人第一次就診時不知所措,手裡拿著一長串轉診單,獨自摸索。我們怎麼能指望那些陷入困境的人在一個只治療局部症狀而忽視整體的體系中找到出路呢?

連接至關重要

在人類歷史的大部分時間裡,生存都依賴我們周圍的村莊。隨著社會變得更加個人主義, 我們已經 忽視了我們的連結有多重要——不僅對個人福祉,而且對社區健康和復原力也至關重要。

護理人員是維持緊張系統正常運作的黏合劑。很多時候 他們是 儘管他們是寶貴的支持和洞察力來源,但他們卻被視為理所當然,甚至受到指責。他們自己的健康 頻繁地 被忽視-只有當他們自己成為病人時才會被注意到。

身為臨床心理學家和澳洲新南威爾斯州關係協會的首席執行官,我了解治療領域的各個方面。 25年來, 我有 了解早期介入(為人們提供建立安全、健康連結的技能和資源)如何改變生活。

衝突加劇、關係破裂、問題不斷出現 不能 被打斷,心理健康就會受到影響。社交孤立不僅影響個人,也影響整個家庭群體,因為朋友會在長期的掙扎中疏遠。

讓人們表達擔憂、制定解決老問題的策略並進行更具建設性的溝通,可以在焦慮或憂鬱出現之前改變生活軌跡。

“讓人們表達擔憂、制定解決老問題的策略並進行更具建設性的溝通,可以在焦慮或抑鬱出現之前改變一個人的生活軌跡。”

Elisabeth Shaw,澳洲新南威爾斯州關係協會首席執行官

我們每天都會看到這樣的事。在我們的諮商室裡,斷絕關係的後果顯而易見:夫妻陷入危機,青少年躲進自己的房間,澳洲老年人遭受家庭成員的虐待,照護人員變得孤立無援。

我們知道,連結是一種保護,但牢固的關係並非偶然建立。它需要透過技能、支持和持續的努力來建立。

連結危機

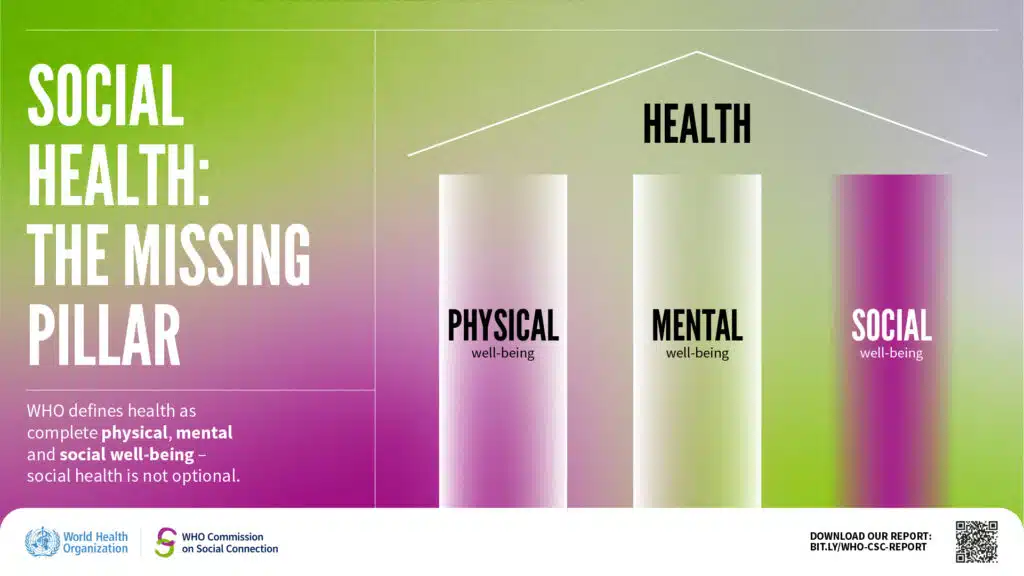

研究越來越證實了從業者早已認識到的道理。世界衛生組織將健康定義為「身體、心理和社會適應的全面健康」。然而,「社會適應」一詞卻被擱置一旁。身體疼痛?去看全科醫生。焦慮?去心理醫生那裡轉診。

但人類天生渴望聯繫。社會福祉是健康的支柱,與身心健康同等重要。人際關係可以緩解壓力,調節我們的神經系統,並幫助我們度過人生中最艱難的時期。

孤獨現在被認為是全球性的健康問題。 六分之一 全世界有許多人感到孤獨,每年約有87萬人因此喪命。孤獨的影響隨處可見──在上班的公車上,人們彼此目光空洞;在夫妻之間,人們感到彼此冷漠;在友情被數位訊息所取代的環境中。

長期孤獨會擾亂免疫系統和消化系統,增強威脅反應,並導致長期健康問題。然而,在我們自己的 民調有 48% 的人表示,他們正在經歷情感困擾,並獨自應對。

那麼,為什麼我們把社交連結視為心理健康的邊緣,而不是核心?為什麼人際關係支持不像看全科醫生那麼容易取得、常規化?

綜合模式是前進的方向

儘管心理健康系統一直有缺陷,但也出現了一些改變的跡象。聯邦政府許多新的心理健康中心正在測試整合模式,將關係服務和生活體驗從業者與心理學家並列。

下週,一家新的Medicare心理健康中心將在新南威爾斯州坎貝爾鎮開業,以全新方式將關係支援融入臨床護理。隨著新南威爾斯州各地越來越多的中心相繼落成,我們看到了協作式、並肩式服務的巨大潛力,這些服務能夠無縫銜接,滿足個人及其社交生活的需求。

這是一個充滿希望的轉變──但這只是個開始。如果我們想要持久的改變,關係支持必須成為心理健康體系的核心,而不是邊緣。

幾十年來,我們一直在傾聽那些最脆弱的人們的心聲,最終得出一個深刻的教訓:人們並不需要完美的生活才能茁壯成長。他們需要的是強大、支持性的網絡,以及能夠認同他們重要性的體系。

密不可分-當我們投資人際關係時,我們也投資了心理健康。